- Leaky Gut Syndrome, Dysbiosis, Nutrition, Foods, Herbs, Phytotherapy

Healing of Leaky Gut Syndrome: Nutrition and Herbal Medicine for intestinal barrier health support

Author: Dr. Andréa Fuzimoto

Disclosure: This site contains links to our stores. Some others may be affiliate links by which we may earn a small commission when you purchase certain products or services. This does not affect the prices that you may pay for them. By purchasing from us you help support this website and our services. Thank you!

As the intestinal barrier is the “biological door” to many illnesses, it also plays an important role in regulating whole-body healing. Foods, herbs and natural phytocompounds are at the functional treatment frontline gently providing modulation of different pathways to regenerate intestinal lining and regulate of microbiota-microbiome.

As insightfully suggested by Fasano, “All disease begins in the (leaky) gut”.1 An increased permeability of the intestinal lining (leaky gut) that permits the passage of toxins, pathogens, and undigested food particles into the blood stream has been associated with several chronic diseases. Regeneration and functional support of the intestinal cell wall is essential and often one of the first steps to restore health. Everything that we eat and drink interacts with the components of our gastrointestinal system including the microbial community (microbiota) and influences our metabolic, hormonal, and immune systems. Thus, foods and herbs may have an impact on different systems and influence one’s health. Some phytocompounds can help regenerate the intestinal and brain barriers.2 However, foods can either disrupt or support the intestinal lining showing the importance of understanding the mechanisms involved in leaky gut to address its dysfunctions.

Phytotherapies for Leaky Gut

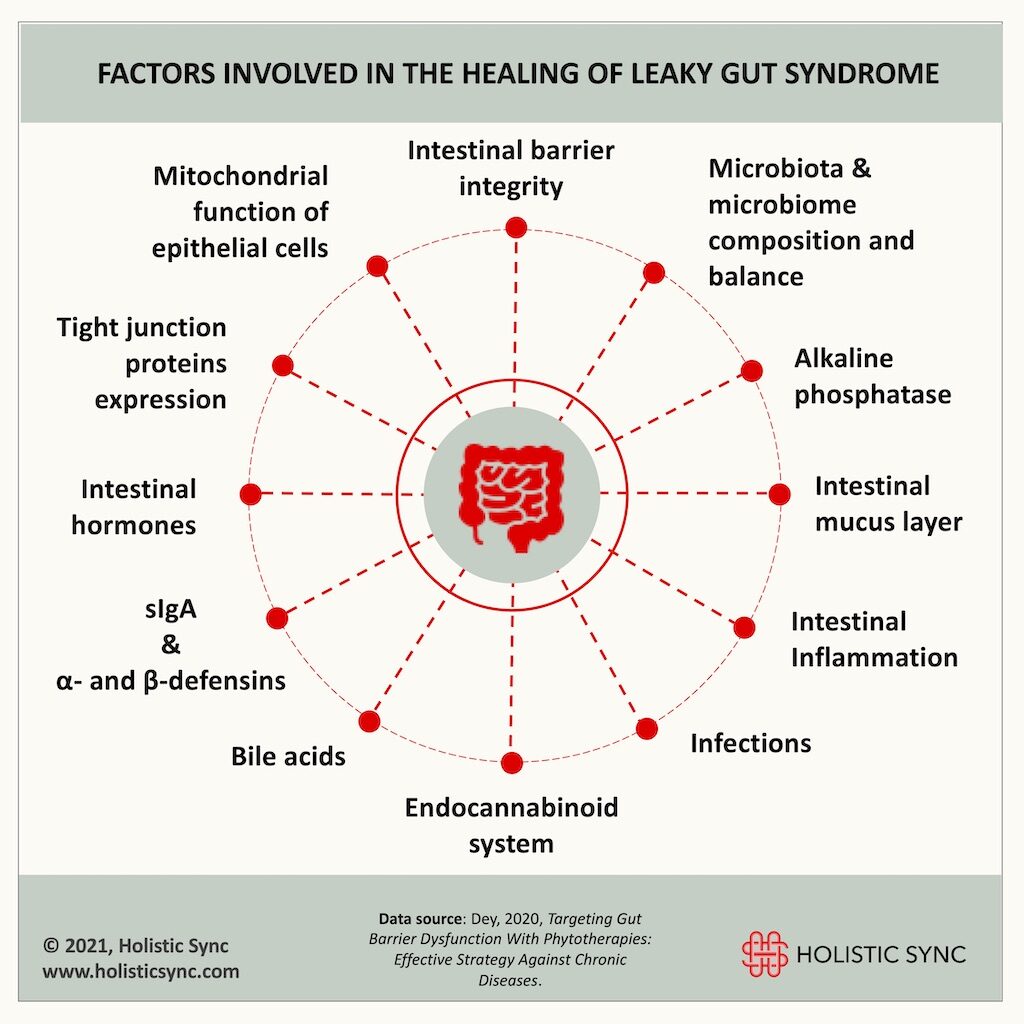

Studies show that good intestinal health depends on several factors such as the status of the intestinal permeability, microbiota-microbiome composition and balance, gut hormones, the intestinal mucous layer, and secretion of gut antimicrobials and antibodies, to cite a few.2 Herbs and phytocompounds can positively affect different pathways involved in the healing of leaky gut.

1. Phytotherapies can improve and maintain intestinal barrier integrity

The lining of the intestines which is composed of epithelial cells provides a functional and physical barrier interfacing the external and internal environments. This barrier keeps pathogens, bacteria toxins, and food particles from crossing over into the bloodstream. Disruption of barrier integrity may cause unwanted substances to translocate into blood vessels leading to a syndrome called “leaky gut”. In turn, this may cause a systemic inflammation present in many diseases.2 Some foods, herbs, and natural compounds seem to improve barrier function such as cruciferous vegetables and the flavonoids quercetin and kaempferol.2 Some of these natural substances work in specific pathways that prevent mucosal inflammatory injury.

2. Phytotherapies can improve tight junction protein (TJP) expression

The intestinal cells are “tied” together by the “tight junctions” which are composed of proteins that regulate the passage of substances into the bloodstream such as ions, solutes, and water.3 The TJPs allow the passage of nutrients while also providing a physical barrier to block pathogens and large harmful molecules. Phytochemicals may also increase the expression of the tight junction proteins and assist in the regeneration of the gut barrier. In one research study, epigallocatechin and catechin present in teas such as green tea regenerated the gut barrier by restoring TJPs.2 Catechins are found in fruits and dark chocolate. Foods that contain the highest amounts of total catechin include dark chocolate, milk chocolate, home-cooked bean, black grapes, blackberries, cherries, apricots, and some apple types.4

3. Phytotherapies can improve the epithelial mucin barrier

The cells of the intestinal wall secrete many defensive compounds into the mucosal fluid to contribute to the physical barrier. Mucins have a critical role in lodging the commensal flora and counteracting infectious diseases.5 In animal models, curcumin, chlorogenic acid, epicatechin gallate (EGCG), and quercetin induced mucin secretion by differential gene expressions and contributed to a healthy barrier function.2

4. Phytotherapies can improve antibodies and antimicrobial secretion

The secretion of the antibody IgA (sIgA) by the epithelial immune cells represents the first line of defense. The sIgA clears antigens, toxins, and pathogenic microorganisms by blocking their access to epithelial receptors, entrapping them in mucus, and facilitating their clearance through peristaltic and mucociliary movements.6 Also, the specialized secretory epithelial cells called the Paneth cells secrete antimicrobial peptides such as α- and β-defensins. Both sIgA and defensins contribute to the preservation of the intestinal barrier and proper immune function. Studies showed that curcumin, and the Traditional medicine formulas Fei Xi Tiao Zhi Tang and Gui Zhi Tang increased the sIgA.2 Also, research showed that herbs and natural compounds may increase defensins. Some examples are andrographolide and dehydroandrographolide (from Andrographis paniculata), isoliquiritigenin (from Glycyrrhiza glabra), and oridonin (from Rabdosia rubescens).2

5. Phytotherapies can influence intestinal dysbiosis to improve gut barrier

The microbiota is the community of microorganisms such as bacteria, archaea, and fungi that populate our digestive tract, and the microbiome is the collective organisms, genome metabolites, and gut environment.7 Alterations in microbiota-microbiome have been observed in several diseases. The gut barrier and the microbiota-microbiome are intimately interconnected. For instance, microbial imbalance (gut dysbiosis) causes intestinal inflammation which in turn can disrupt the intestinal barrier and may cause a “leaky gut” syndrome. On the other hand, commensal microbes release antibacterial and anti-inflammatory substances, thus assisting the healing of the intestinal wall. Research papers show that several phytotherapy products can modulate the microbiota thus affecting the gut barrier.2 Some examples are Glycyrrhiza glabra root (licorice), European blueberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), and Orange Solomon’s Seal (Polygonatum Kingianum). Catechin-rich green tea may also prevent dysbiosis, improve microbial diversity, and increase microbiota-producing anti-inflammatory products (e.g. short-chain fatty acids).2

6. Phytotherapies can improve gut barrier by targeting inflammation and oxidative stress

Intestinal inflammation lowers the expression of tight junction proteins and intracellular cytoskeletal proteins.2 Also, the imbalance of the redox mechanism affecting the mitochondria of the intestinal epithelial cells can induce barrier dysfunction and breakage.2 Therefore, addressing inflammation and oxidative injury is also important to restore gut health and support normal barrier function. Some examples of natural products that decrease inflammation to support the intestinal wall are curcumin, Japanese maple (Acer palmatum), β-sitosterol from Saw palmetto and other sources, loquat (Eriobotrya japonica), catechin-rich extract (from Camelia sinensis). The herbs and natural compounds that may attenuate oxidative stress of the gut epithelial cells include puerarin (from Pueraria lobate), Jasonia glutinosa, and proanthocyanidin-rich grape seed extract. The mechanisms by which some of these herbs act involve the increase of catalase, glutathione, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels.2

7. Phytotherapies can restore barrier function by upregulating alkaline phosphatase

Intestinal alkaline phosphatase (IAP) is an enzyme secreted by gut epithelial cells. It relieves inflammatory mediated disorders and assists in gut homeostasis maintenance.8 Loss of IAP expression is associated with higher gut inflammation, dysbiosis, bacterial translocation through the gut barrier, and consequent systemic inflammation.8 IAP also detoxifies bacterial endotoxins (lipopolysaccharides-LPS) and specific bacterial proteins called pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs).2 Studies show that curcumin, pepper, ginger, and the compounds piperine and capsaicin can improve intestinal alkaline phosphatase with consequent modulation of gut mucosa structure and membrane.2

8. Phytotherapies can protect bile acids-dependent barrier

Bile acids are steroids made by the liver cells that are concentrated for storage in the gallbladder and secreted into the bile. Secondarily, they are also metabolized by microbiota. The main function of the bile is to emulsify fats and facilitate digestion. The other functions of the bile acids are to excrete cholesterol and they also have an antimicrobial effect. The bile acids modulate gut-barrier by interacting with intestinal receptors.2 Also, the microbiome regulates bile acid pool size, and reduced levels of bile acids are associated with bacterial overgrowth and inflammation.9 This connection between the gut microbiome and bile acids is called the “bile acid-gut microbiome axis”.9 Phytotherapies that increase the bile acids and receptors expression may decrease intestinal permeability and mucosal inflammation. Some examples are bitter orange (Citrus aurantium) and blueberry extract.2

9. Phytotherapies can regulate the endocannabinoid system

The endocannabinoid system (ECS) controls a series of gastro-intestinal functions including motility, gut-brain-mediated fat intake and hunger signaling, inflammation and gut permeability, and it interacts with the gut microbiota.10 For instance, the activation of intestinal endocannabinoid receptors inhibits peristalsis and gastric acid secretion, and increases food intake.10 It was proposed that the ECS interacts with the gut microbiome to regulate the gut barrier function.2 Dysfunction of the ECS may play a role in intestinal disorders such as inflammatory bowel diseases, irritable bowel syndrome, and obesity.10 Resveratrol which is present in several herbs and natural products (e.g. Japanese Knotweed, grapes, blueberries, and cranberries) may improve barrier dysfunction by downregulating mRNA expression of the cannabinoid receptors (CB1 and CB2).2

10. Phytotherapies can modulate gut hormones to provide barrier protection

Some specific intestinal hormones may regulate barrier function such as glucagon-like peptide-1 and 2 (GLP-1 and GLP-2). For instance, the GLP-2 secreted by the intestinal epithelium increases intestinal cell proliferation, inhibits programmed cell death (apoptosis), enhances barrier function, and improves digestion, absorption, and blood flow.11 Some herbs and natural compounds can increase these hormones and contribute to preserving barrier function. Some examples are ginsenoside Rb (from Panax ginseng), berberine (from berberine-rich herbs such as Coptidis rhizome and Berberis vulgaris or barberry), and yacón (Smallanthus sonchifolius).2

Other factors and molecular pathways are involved in gut health, and many other herbs and natural compounds not mentioned in this article may decrease intestinal permeability and support barrier function. The subject is very extensive and cannot be fully covered here. Other resources also include vitamins and minerals such as vitamin D, vitamin A, and zinc. Research shows that vitamins A and D regulate the expression of the tight junction proteins of the intestinal lining to support the barrier and immune system, and modulate microbial communities in the gut.12 In some studies, zinc also improved barrier function. Thus, supplementing with these vitamins may help in recovering and maintaining intestinal health. It is also important to remember that, infections such as bacterial (e.g., H. pylori, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth-SIBO), fungal, and parasitic infections may disrupt the gut barrier and need to be addressed before-while restoring barrier health. Lifestyle modifications may also be needed. Since breakage of the gut barrier increases with age, we need gentle and safe resources to address it. Nutrition is one of the best ways to manage gut health since it modulates gut microbiota-microbiome, and in turn, it supports the gut barrier.

Dr. Andréa Fuzimoto, DAOM, MSTCM, MSCS, CSAS, Dipl. O.M (NCCAOM®/USA), L.Ac. (CA/USA); PT/Acu (BR) is a clinician and researcher working with Holistic Integrative Medicine (HIM) with emphasis in gastrointestinal, neurological, and immunological conditions. Patients look for her careful diagnostic evaluation, strategic treatment planning, and compassionate care. As a researcher, she is a peer-reviewed published author and a certified peer-reviewer contributing to different scientific journals. She has trained and worked in centers of excellence such as the Stanford University Medical School (Pain Medicine Division) with NIH-funded Clinical Trials, and the California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC), at the Stroke Clinic, among others. For more information on her specialties and certifications, visit Linkedin.

References:

- Fasano A. All disease begins in the (leaky) gut: role of zonulin-mediated gut permeability in the pathogenesis of some chronic inflammatory diseases. F1000 Res. 2020;(Faculty Rev-69). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.12688%2Ff1000research.20510.1

- Dey P. Targeting Gut Barrier Dysfunction With Phytotherapies: Effective Strategy Against Chronic Diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2020;(161:105135). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105135

- Lee B, Moon K, Kim C. Tight Junction in the Intestinal Epithelium: Its Association with Diseases and Regulation by Phytochemicals. J Immunol Res. 2018;(2018:2645465). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1155%2F2018%2F2645465

- Arts I, de Putte B, Hollman P. Catechin Contents of Foods Commonly Consumed in The Netherlands. 1. Fruits, Vegetables, Staple Foods, and Processed Foods. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;(48,5, 1746-1751). doi:https://doi.org/10.1021/jf000025h

- Linden S, Sutton P, Karlsson N, Korolik V, McGuckin M. Mucins in the mucosal barrier to infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;(1, 183-197). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fmi.2008.5

- Mantis N, Rol N, Corthésy B. Secretory IgA’s Complex Roles in Immunity and Mucosal Homeostasis in the Gut. Mucosal Immunol. 2011;(4(6):603-611). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fmi.2011.41

- Valdes A, Segal E. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ. 2018;(361:k2179). doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179

- Fawley J, Gourlay D. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase: a summary of its role in clinical disease. J Surg Res. 2016;(202(1):225-34). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.12.008

- Ridlon J, Kang D, Hylemon P, Bajaj J. Bile Acids and the Gut Microbiome. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;(30(3):332-338). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FMOG.0000000000000057

- DiPatrizio N. Endocannabinoids in the Gut. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016;(1(1):67-77). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1089%2Fcan.2016.0001

- Markovic M, Brubaker P. The roles of glucagon-like peptide-2 and the intestinal epithelial insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in regulating microvillus length. Sci Rep. 2019;(9:13010).

- Cantorna M, Snyder L, Arora J. Vitamin A and vitamin D regulate the microbial complexity, barrier function and the mucosal immune responses to insure intestinal homeostasis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;(54(2):184-192). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1080%2F10409238.2019.1611734

- Kharrazian D. The Gluten, Leaky Gut, Autoimmune Connection (Seminar Manual).; 2013.

- Martinez K, Leone V, Chang E. Western diets, gut dysbiosis, and metabolic diseases: Are they linked? Gut Microbes. 2017;(8(2):130-142). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2016.1270811

- Brahe L, Astrup A, Larsen L. Can We Prevent Obesity-Related Metabolic Diseases by Dietary Modulation of the Gut Microbiota?1. Adv Nutr. 2016;(7(1):90-101). doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.3945%2Fan.115.010587