- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE), Autoimmune Diseases, Inflammation, Herbal Medicine

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) and Herbal Medicine.

Author: Dr. Andréa Fuzimoto

Disclosure: This site contains links to our store. Some others may be affiliate links by which we may earn a small commission when you purchase certain products or services. This does not affect the prices that you may pay for them. By purchasing from us you help support this website and our services. Thank you!

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is considered by some researchers as a new epidemic reflected on the ongoing challenges in diagnosis and treatment.1,2 Advancements in Phytomedicine research highlight potential treatment options for the growing SLE cases. Some herbs and natural compounds possess very similar mechanisms to the pharmaceutical drugs being used and researched for SLE. This incites hope that, in the future, clinicians may rely on non-toxic and highly bioavailable herbal products to treat and manage SLE in a very targeted approach.

In 2017, North America had the highest incidence and prevalence of SLE in the world estimated at 23.2/100,000 person-years in the U.S., and 241/100,000 person-years in Canada.3 Conversely, the lowest incidence of SLE was reported in Africa and Ukraine (0.3/100,000 persons-year). In the U.S., the annual prevalence of SLE went from 81.07/100,000 in 2003 to 102.94/100,000 in 2008.4 Women represented a higher incidence of the disease if compared with men (2:1 to 15:1), and the age of new occurrences ranged from the 30s to 70s3. These numbers account for a good portion of the population who are surely eager to participate in the active workforce and be productive but often find themselves unable due to the disease. Work disability can get as high as 23%.

SLE can be aggressive when left untreated affecting several organ systems such as kidneys, lungs, skin, and the central nervous system. A more recent study (2021) was able to give a more precise assessment of the number of SLE cases and disease prevalence in the US in 2018 using the CDC National Lupus Registry network.5 The research showed a prevalence of 72.8 per 100,000-years, and it was estimated 9 times higher among females than males. Stratified results showed the prevalence for females (128.7 per 100,000), highest for black females (230.9 per 100,000), followed by Hispanic females (120.7 per 100,000), white females (84.7 per 100,000), and Asian/Pacific Islander females (84.4 per 100,000). Given this results, the SLE number of cases in the US may have been underestimated by previous studies or they may be indeed rising.

The SLE pharmaceutical treatment aims to control the disease activity, prevent flares, minimize irreversible buildup damage, avoid drug toxicity, and improve the patient’s quality of life.5 The medications frequently used for SLE include hydroxychloroquine, glucocorticoids, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, cyclosporine A, and biological medications such as rituximab and belimumab.5 Hydroxychloroquine is almost universally prescribed because it offers multiple benefits such as lowering disease activity, prevention of metabolic syndrome and disease manifestations, protection from infections, correction of lipid abnormalities, and other benefits.5 However, despite the pharmacological efforts, many SLE patients still experience disease activity and flare-ups, accumulated toxicity due to the use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressant drugs, and lingering symptoms even after being considered in “remission”.5 Moreover, treatment compliance poses a challenge to many SLE patients.

Treatment compliance to SLE Drugs

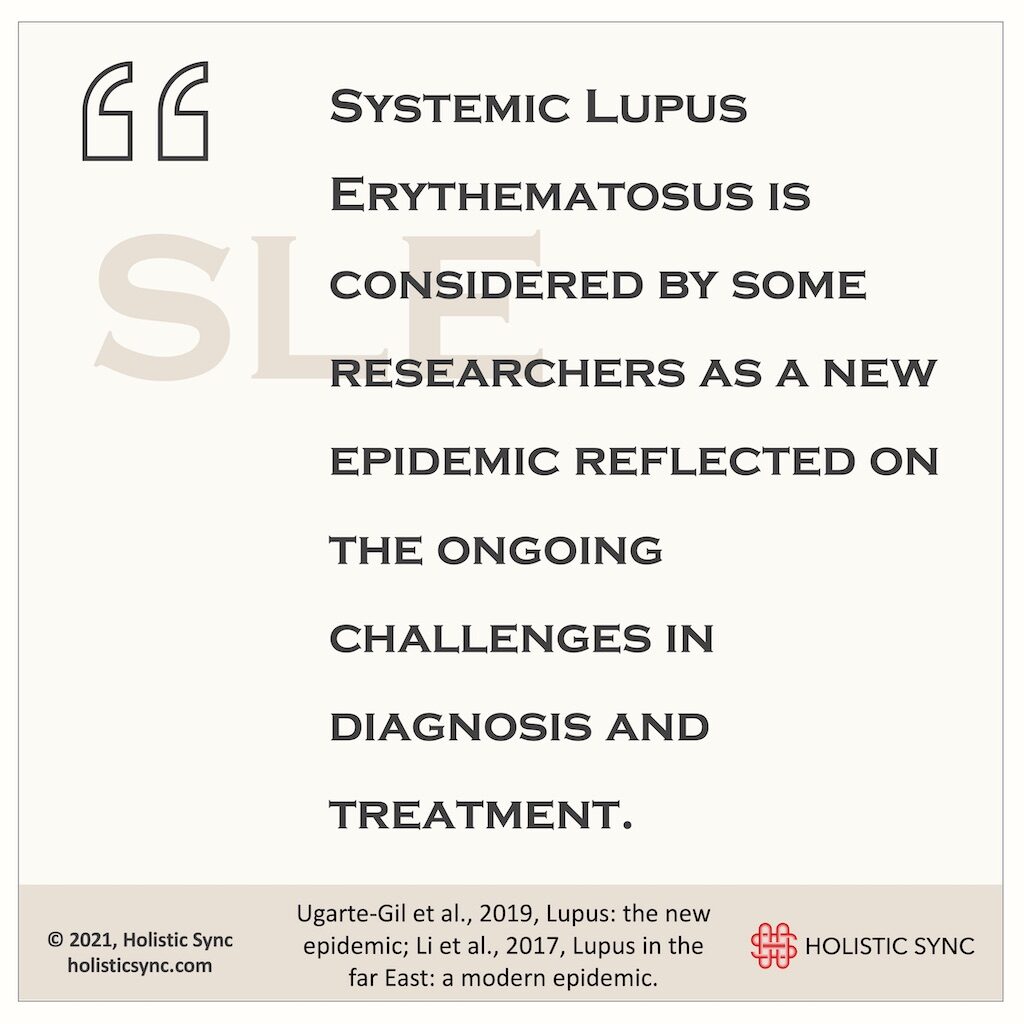

A study from John Hopkins University (2018) revealed that despite treatment advancements, mortality among SLE patients remains high6. In addition, the lack of adherence to the prescribed drugs is a common problem among SLE patients. Based on a pharmacy refill study (2008), only 49% of the patients were adherent to hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), 61% to prednisone, and 57% to other immunosuppressant medications.7 For this study, the adherence level to achieve a therapeutic response was 80%.³

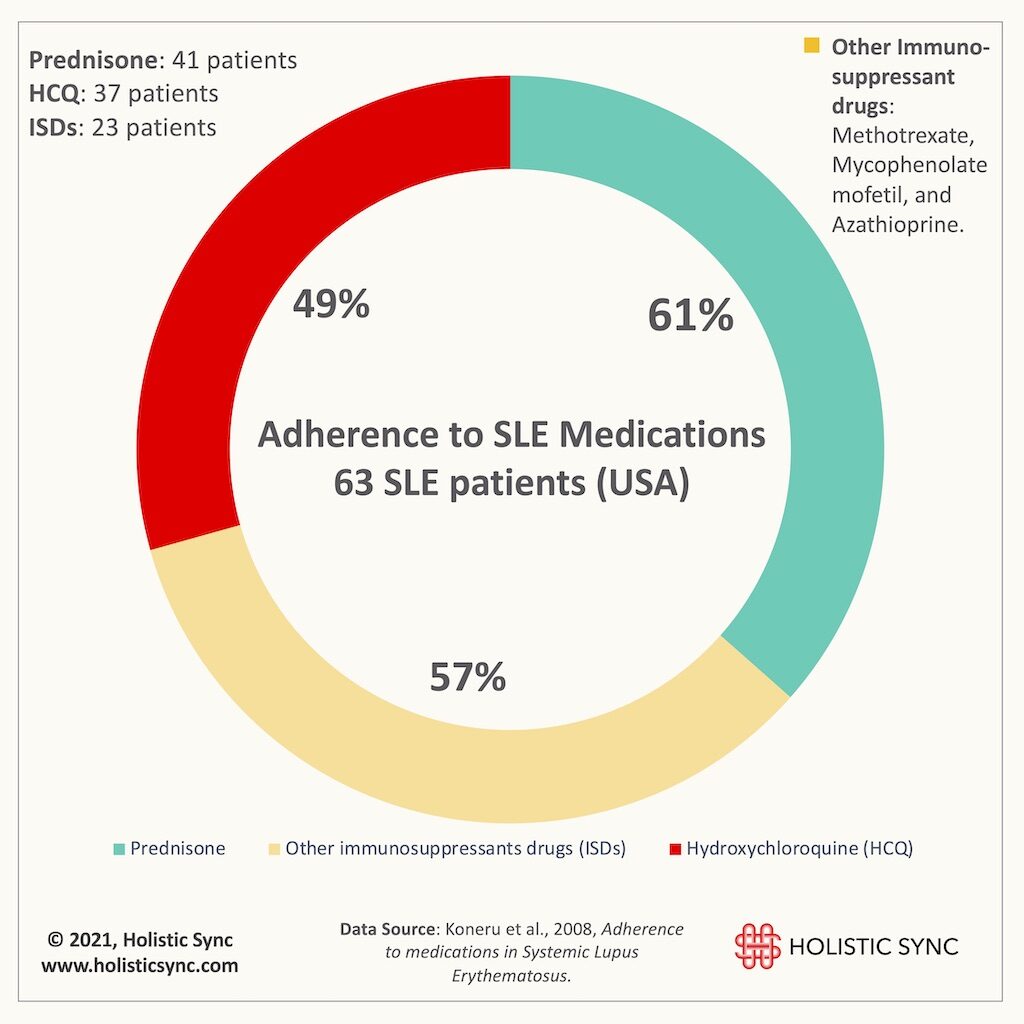

In a more recent study (2018), almost 64% of the 72 SLE patients were non-adherent to drug treatment, and adherence to HCQ was the lowest (33.3%).8

The reasons for non-compliance included forgetfulness, running out of medication, being too busy at work, not being at home, high cost of the drugs or having no money for them, lack of understanding of the instructions on how to take them, and comorbidities, to cite a few.7,8 Some patients just don’t organize themselves and need a reminder system to comply, while others feel sicker, experience intolerance and side effects, or feel no effects from the medications.7,8

The results on the efficacy of rituximab are controversial. Many clinical trials failed to show improvements in renal and non-renal lupus patients while many physicians have a positive clinical experience and advocate for its use.9 Belimumab is the first biological FDA- and EU-approved drug for SLE as add-on therapy in adult patients for the non-renal type of disease.10 In a real-world study of intravenous administration of belimumab, the adherence to the medication was low with 26.6% of the patients discontinuing it in the 6-month post-index period.11 Both rituximab and belimumab can present adverse effects from mild to more severe complications.12,13 Despite the signs of progress in the therapeutic options for SLE, we still seem far from a perfect solution that provides a smooth resolution of symptoms with no risks and adverse effects. Many SLE patients can adhere to the medications for a lifetime or periods of time, but many others cannot. When faced with the impossibility to comply with the conventional treatments, many SLE patients report using Complementary and Alternative Medicines (CAMs), including herbs and phytocompounds. But, you may be asking yourself right now, “what is the evidence on herbs for SLE”, and “how would they compare with conventional medications”?

Mechanism of action of biological drugs for SLE

To understand the potential action of Phytomedicine for SLE, first, we need to be aware of what happens during the disease and how some drugs work. SLE is characterized by defective immune regulatory mechanisms and B cell dysregulation is the hallmark of SLE.14 A common pathophysiological process that occurs in SLE is the hyperactivity of T helper cells that promote differentiation and activation of B cells, which in turn lead to antibody production. These antibodies attack components of the cell nucleus and form immune complexes that deposit in blood vessels causing inflammation, vasculitis, vasculopathy, and tissue damage14. The strategy of biological drugs for SLE such as rituximab and belimumab is to block the pathways involved in the B cell differentiation and activation, which in turn leads to a reduction of pathogenic antibody makeup. For example, rituximab targets CD20, the protein expressed on the surface of B cells to reduce their numbers15. Belimumab aims to inhibit the B lymphocyte stimulator (BLyS) which is involved in B cell differentiation. Basically, the biological medications have the goal of hindering the B cells to consequently decrease antibody production. Recent studies are bringing evidence to light showing that some herbs and phytochemicals may help in the management of SLE patients by targeting the same or very similar pathways, while also promoting other biological effects.

Three potential herbs for SLE

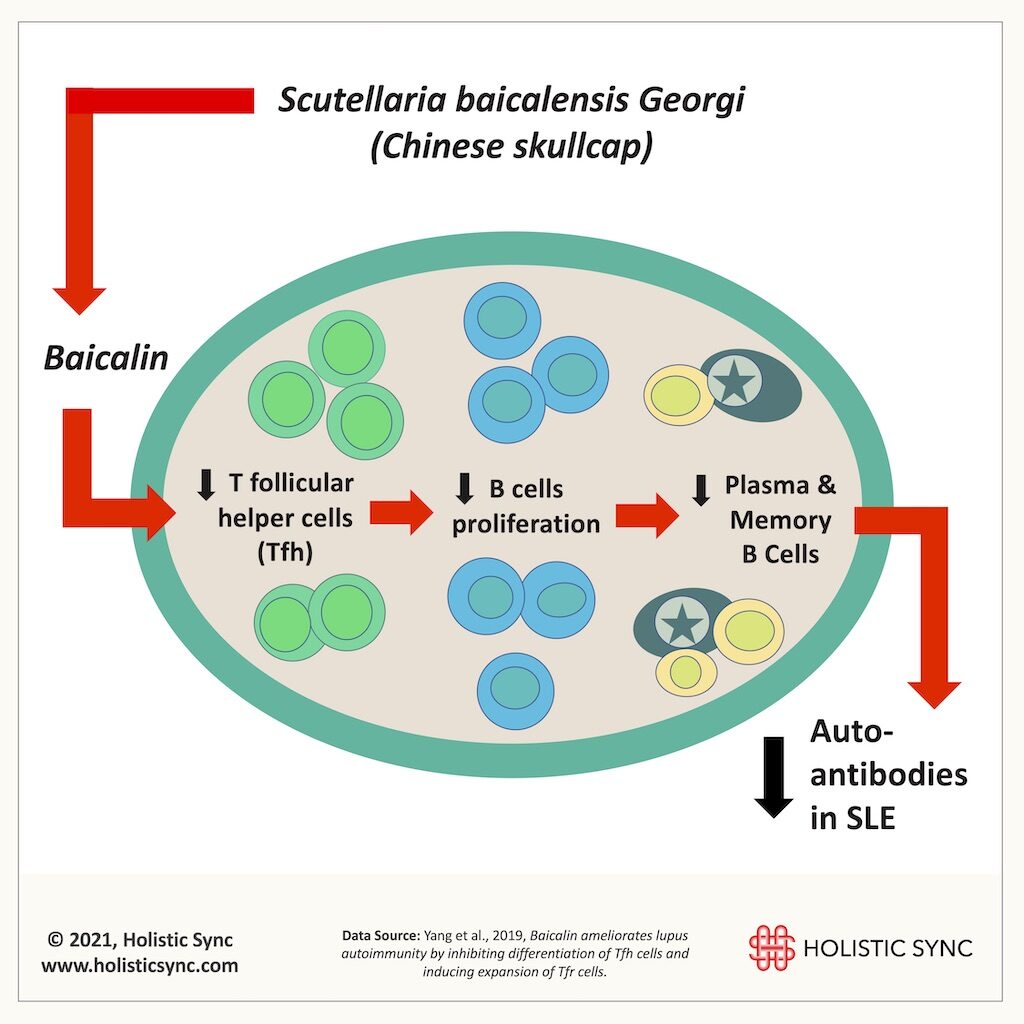

1. Scutellaria baicalensis

Baicalin is a compound extracted from Scutellaria Baicalensis, a popular herb used for many ailments and well known for its anti-inflammatory effects. In this study (2019), baicalin improved lupus nephritis, reduced urine protein, and antibody titers (ds-DNA) in an animal model of SLE.16 Baicalin inhibited interleukin-21 (IL-21) and T follicular helper cells (Tfh) differentiation in vivo and in vitro. The downregulation of these T helpers cells caused a reduction of B cell proliferation and differentiation, leading to a decrease in auto-antibodies.16 Also, baicalin induced Foxp3+ regulatory T cells which are known to prevent autoimmunity, increase self-tolerance, and reduce inflammation, among other functions.16 Thus, baicalin showed a great potential to assist in the treatment of SLE.

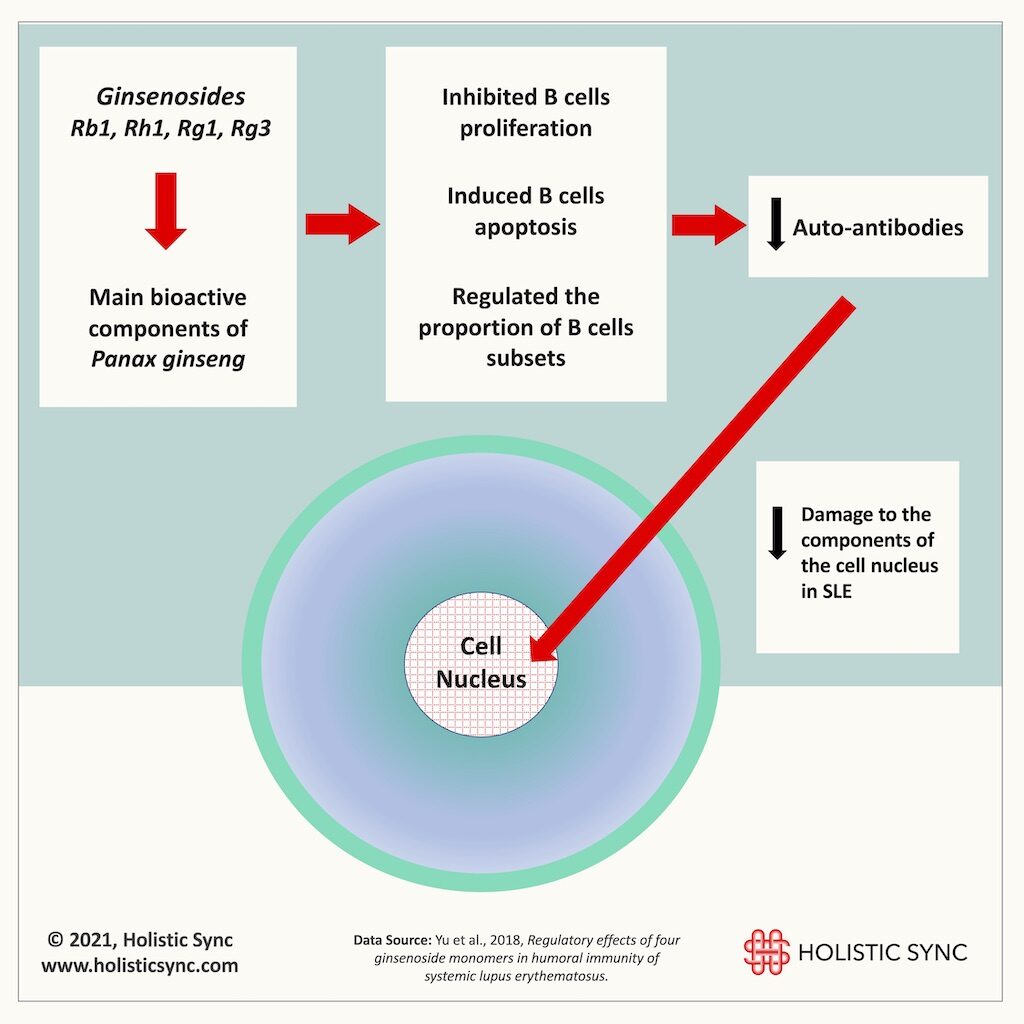

2. Panax ginseng

Panax ginseng is another very well-known and researched herb for many diseases and ginsenosides are the main bioactive compounds extracted from it. In this in vitro study (2018), the ginsenosides Rb1, Rh1, Rg1, and Rg3 inhibited the proliferation of different B cell subsets and prompted their “cell death” (apoptosis).17 Upon measuring the antibodies produced by the B cells, the researchers verified that the ginsenosides caused a reduction of antibody production thus minimizing the damage to the components of the cell nucleus.17 Therefore, Panax ginseng and ginsenosides are interesting prospective remedies for SLE.

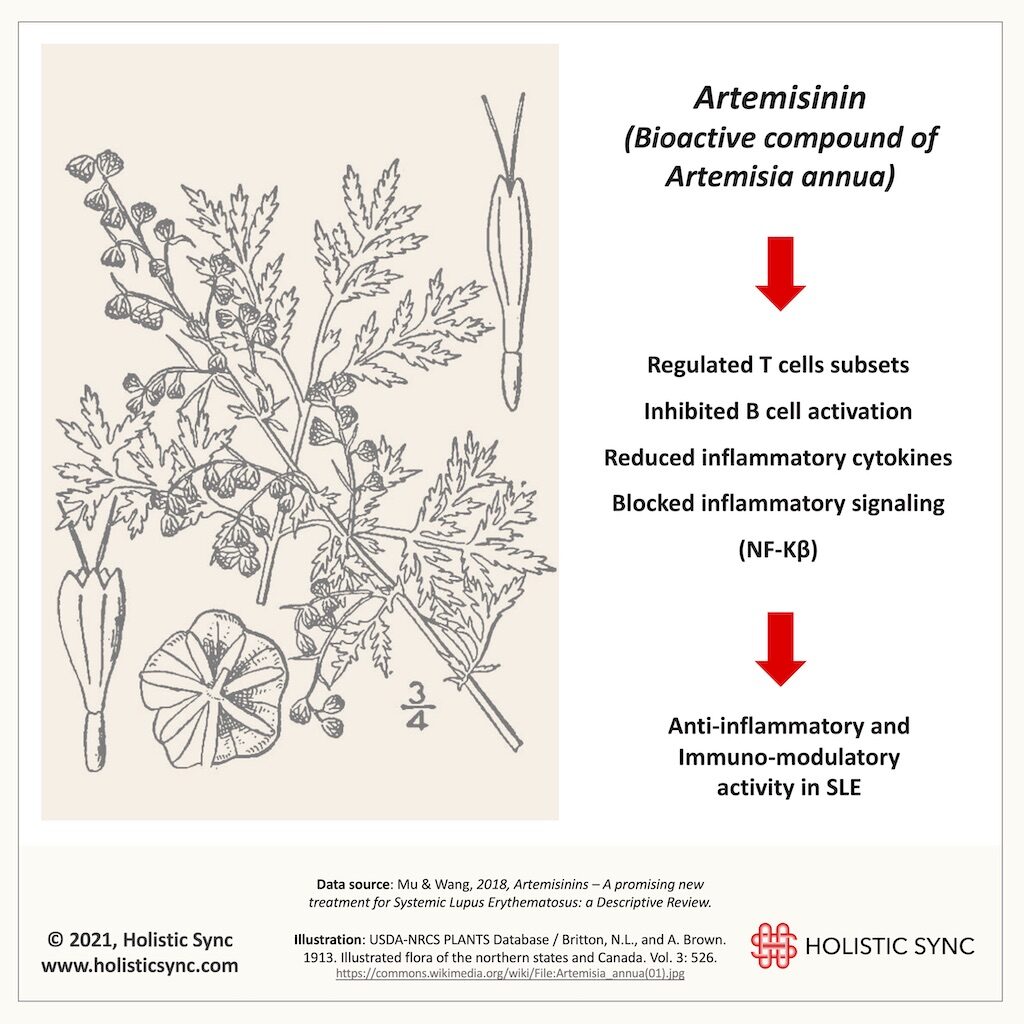

3. Artemisia annua

Artemisia annua has a long history in the clinical application for many diseases and it is well known for its antimalarial, anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive, and anti-cancer properties. Artemisia annua has several bioactive derivatives including artemisinin and artesunate. In 2015, Dr. Tu Youyou from the Institute of Chinese Materia Medica and the Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (China) received the Nobel prize in Medicine or Physiology for her long-life achievements in the discovery and extraction methods of artemisinin. As a result of her team’s research and other investigation groups, currently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends artemisinin-based combination therapy as the first-line treatment for multi-drug-resistant malaria. Animal studies on artemisinin for SLE showed that it can regulate T cells, inhibit B cell activation, and reduce inflammatory markers18. Thus, A. annua and artemisinin are likely candidates to slow the course of SLE disease and manage symptoms. Interestingly, hydroxychloroquine which is an antimalarial drug has also been extensively used for SLE for quite some time.

These in vitro and in vivo studies on SLE utilizing baicalin (from Scutellaria baicalensis), ginsenosides (from Panax ginseng), and artemisinin (from Artemisia annua) inhibited B cell activity, downregulated the production of pathogenic antibodies, and reduced cell damage. The mechanism of action of these herbs is similar to the biological drugs in which they downregulated the activation and proliferation of B cells. Many other herbs, phytochemicals, and herbal formulas are being researched for SLE. Although the herbal studies mentioned here do not aim to inform clinical practice, they provide a snapshot of their mechanisms and the potential to assist in the treatment of SLE. Advantages of using herbs and phytocompounds include the fact that many of them, generally speaking, may have low or no toxicity, good solubility, and high bioavailability. Furthermore, many herbs and phytocompounds have consistently proved their biological properties such as immune-modulatory and anti-inflammatory. However, many herbs could be unsuitable for treatment, for example, due to the needed higher dosages to attain results which could increase toxicity. Some herbs may need special formulations such as herbal-loaded lipid-nanocarriers or nanoparticles to increase bioavailability. Importantly, since some herbs have similar mechanisms to pharmaceutical drugs, their concomitant administration may cause drug-herbal interactions (good or bad). Thus, many factors should be considered in the herbal investigations and treatment for autoimmune diseases. Nonetheless, the above examples offer an exciting perspective where Phytomedicine research for SLE may be heading in the next years.

Dr. Andréa Fuzimoto, DAOM, MSTCM, MSCS, CSAS, Dipl. O.M (NCCAOM®/USA), L.Ac. (CA/USA); PT/Acu (BR) is a clinician and researcher working with Holistic Integrative Medicine (HIM) with emphasis in gastrointestinal, neurological, and immunological conditions. Patients look for her careful diagnostic evaluation, strategic treatment planning, and compassionate care. As a researcher, she is a peer-reviewed published author and a certified peer-reviewer contributing to different scientific journals. She has trained and worked in centers of excellence such as the Stanford University Medical School (Pain Medicine Division) with NIH-funded Clinical Trials, and the California Pacific Medical Center (CPMC), at the Stroke Clinic, among others. For more information on her specialties and certifications, visit Linkedin.

References

- Ugarte-Gil M, González L, Alarcón G. Lupus: the new epidemic. Lupus. 2019;(Vol:28; issue:9; Pages 1031-1050). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0961203319860907

- Li P, Lau C. Lupus in the far east: a modern epidemic. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;(20(5):523-525). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1756-185x.13115

- Rees F, Doherty M, Grainge M, Lanyon P, Zhang W. The Worldwide Incidence and Prevalence of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Studies. Rheumatol Oxf. 2017;(56(11):1945-1961). doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/rheumatology/kex260

- Furst D, Clarke A, Fernandes A, Bancroft T, Greth W, Iorga S. Incidence and Prevalence of Adult Systemic Lupus Erythematosus in a Large US Managed-Care Population. Lupus. 2013;(22(1):99-105). doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961203312463110

- Fanouriakis A, Bertsias G. Changing paradigms in the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus Sci Med. 2019;(6(1):e000310). doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/lupus-2018-000310

- Stojan G, Petri M. Epidemiology of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: an update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;(30(2):144-150). doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/bor.0000000000000480

- Koneru S, Kocharla L, Higgins G, et al. Adherence to Medications in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. 2008;(195-201). doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/rhu.0b013e31817a242a

- Prados-Moreno S, Sabio J, Pérez-Mármol J, Navarrete-Navarrete N, Peralta-Ramírez M. Adherence to Treatment in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Med Clínica. 2018;(Volume 150, Issue 1, Pages 8-15). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medcle.2017.11.023

- Beckwith H, Lightstone L. Rituximab in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and Lupus Nephritis. Nephron Clin Pr. 2014;(128(3-4):250-4). doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000368585

- Blair H, Duggan S. Belimumab: A Review in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Drugs. 2018;(78(3):355-366). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-018-0872-z

- Bell C, Priest J, Stott-Miller M, et al. Real-world Treatment Patterns, Healthcare Resource Utilisation and Costs in Patients With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Treated With Belimumab: A Retrospective Analysis of Claims Data in the USA. Lupus Sci Med. 2020;(7(1):e000357). doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/lupus-2019-000357

- Rituximab – Possible Side Effects of Rituximab. Retrieved on Jun 12, 2020. https://rituximab.com

- BENLYSTA: 9 YEARS IN-MARKET EXPERIENCE – Retrieved on Jun 12, 2020. https://gskpro.com/en-us/products/benlysta/adverse-reactions/

- Mok CC, Lau C. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. J Clin Pathol. 2003;(56(7):481-90). doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.56.7.481

- Pescovitz M. Rituximab, an anti-cd20 Monoclonal Antibody: History and Mechanism of Action. Am J Transpl. 2006;(6(5 Pt 1):859-66). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01288.x

- Yang J, Yang X, Yang J, Li M. Baicalin ameliorates lupus autoimmunity by inhibiting differentiation of Tfh cells and inducing expansion of Tfr cells. Cell Death Dis. 2019;(10(2):140). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-019-1315-9

- Yu X, Zhang N, Lin W, et al. Regulatory effects of four ginsenoside monomers in humoral immunity of systemic lupus erythematosus. Exp Ther Med. 2018;(15(2):2097-2103). doi:https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.5657

- Mu X, Wang C. Artemisinins—a Promising New Treatment for Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: a Descriptive Review. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;(20(9):55). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-018-0764-y